Why Do Plastic Dust Explosions Keep Killing Workers?

.jpg.2602191322066.webp)

Most people don't think of plastic as something that can explode. It's one of the most common, seemingly harmless materials in everyday life, the stuff of water bottles, food packaging, and phone cases. But inside the facilities that manufacture, process, and recycle plastic, that same material takes on a completely different character. Ground into fine dust, suspended in the air, and confined in an enclosed space, plastic becomes an explosive hazard that rivals aluminum powder, grain dust, and other known dangers.

Between 1980 and 2005, the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board (CSB) documented 281 combustible dust incidents that killed 119 workers and injured 718 more across 44 states. Plastics, along with rubber and synthetic resins, ranked among the most dangerous materials involved.

While these events are relatively common, they are far from inevitable. Plastic dust explosions keep happening, not because the hazard is poorly understood, but because the same preventable failures repeat themselves, time and time again, in facility after facility, year after year. In most cases, workers are simply doing exactly what they were hired to do: run equipment, clean up, perform routine maintenance. It’s when the conditions for an explosion quietly build for weeks, months, even years, that disaster can strike, seemingly without warning.

But what, exactly, causes plastic dust explosions? To understand how something so ordinary can become so deadly, you first have to understand what happens to plastic inside these facilities and how explosive conditions can arise.

What Happens Inside a Plastics Facility

In a traditional plastics manufacturing plant, raw material typically arrives as pellets, powders, or sheets. It's heated, molded, extruded, cut, and trimmed into products. Scrap and offcuts are fed back through grinders and granulators to be reused. In plastics recycling facilities, the process involves sorting, shredding, washing, and grinding post-consumer waste (think: bottles, containers, mixed plastics) into flakes or pellets for reprocessing.

Every one of these steps generates fine plastic particles. Every time a granulator chews through scrap material, every time pellets collide inside a pneumatic transport line, every time a blade trims an extruded product, it creates a certain amount of fine dust. And that dust settles everywhere, from obvious places like floors and the tops of equipment to far less noticeable spots, such as inside ductwork, on overhead beams or rafters, above suspended ceiling tiles, and deep inside dust collection systems. In high-volume facilities, accumulated dust can coat surfaces throughout the building, including areas that are rarely cleaned or inspected.

Here's the part most people don’t realize: A layer of settled dust just 1/32 of an inch thick—thinner than a dime—covering as little as 5% of floor area creates enough fuel for a catastrophic explosion if that dust is disturbed and forms a cloud.

Why Plastic Dust Explodes

A solid block of plastic is difficult to ignite but grind it into particles smaller than a grain of sand, and you've dramatically increased its surface area relative to its mass. More surface area means more contact with oxygen, which means faster combustion. What burns slowly as a solid can detonate in a fraction of a second as a dust cloud.

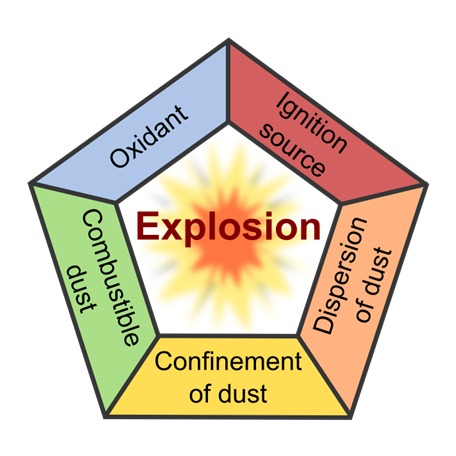

For a dust explosion to occur, five conditions must exist simultaneously. These conditions are what safety engineers call the "dust explosion pentagon."

The Dust Explosion Pentagon. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dust_Explosion_Pentagon.svg#Licensing

The elements of the dust explosion pentagon include:

- Combustible fuel (in this case, the dust itself)

- Oxygen (i.e., the ambient air in the room)

- An ignition source

- Dispersion of the dust into an airborne cloud

- Confinement within an enclosed space

When you remove any single element, an explosion cannot happen. The problem, however, is that inside a plastics facility, all five elements are present during normal operations.

Plastic Dust Is Especially Explosive

Dust explosions are always dangerous, but plastic dust is particularly explosive. The standard measure of explosion severity, known as the Kst value, rates polyethylene dust at 510 bar-meters per second (bar.m/s) and polystyrene at 480 bar.m/s. Both are classified as St3, or the highest category, meaning "very strong explosion." For context, grain dust, the material behind many of the dust explosions that make headlines, registers at just 190. Sugar comes in at 340. Wheat flour at 250. In other words, polyethylene dust is more explosive than nearly every organic material that regulators already worry about.

What’s more, it doesn't take much to set it off. Fine polyethylene dust can ignite from a spark of just 10 to 30 millijoules, roughly the same static discharge a person generates by scuffing their shoes across a carpet. Since plastic is a natural insulator, it builds enormous static charges during processing. Conveyor belts, pneumatic lines, and grinding equipment silently accumulate the energy needed to trigger an ignition without anyone noticing.

Other common ignition sources inside these facilities include overheated bearings, friction from jammed equipment, electrical faults, and sparks from welding or cutting work performed near areas where dust has accumulated.

How a Spark Becomes a Catastrophe

The deadliest feature of dust explosions is the chain reaction between primary and secondary blasts, and it's the mechanism that most people, including many workers and facility managers, don't fully understand.

Here’s an example of how it can work:

- The Primary Blast: A small initial explosion occurs inside a piece of equipment, such as a dust collector, the housing for a grinder, or a conveyor enclosure. This primary explosion may be relatively contained. But the blast wave it sends out doesn't just cause damage; it dislodges accumulated dust from every surface it reaches: beams, ledges, equipment housings, ductwork, ceiling spaces. All that settled dust is suddenly lofted into a massive, airborne cloud that quickly fills the room or the entire building.

- The Secondary Blast: Milliseconds later, the flame front from the primary explosion reaches this newly suspended dust cloud and detonates it. This secondary explosion is orders of magnitude more powerful than the first. It's the secondary blast that collapses structures, kills workers, and sends burning debris for miles. This is why dust accumulation throughout an entire facility matters so much. The dust sitting on a rafter 50 feet from the ignition point can become fuel for the blast that brings the building down.

These events happen fast, and workers typically have no warning. Even at explosive concentrations, dust clouds can be invisible to the naked eye, and ignition is instantaneous. Blast waves travel faster than any person can react. As a result, these explosions are nearly always catastrophic.

Plastic Dust Explosions Happen During Routine Work, Not Emergencies

One of the most important things to understand about plastic dust explosions is when they happen. These aren't events triggered by unusual circumstances or emergency situations. The vast majority occur during completely ordinary operations, from normal production runs to routine cleaning to scheduled maintenance, equipment startups, shutdowns, and the clearing of jammed material.

So often, workers are simply doing their jobs, the same tasks they've performed safely dozens or even hundreds of times before when conditions they didn't create and may not even know about converge into an explosion. That's what makes the pattern so troubling, and why investigations keep pointing back to the same conclusion: these are systemic failures, not situational ones.

Plastic Dust Explosions Expose a Pattern of Preventable Disasters

The history of plastic dust explosions in the United States is not a story of isolated, unpredictable events. It's a pattern, the same failures repeated at different facilities in different states across different decades.

In January 2003, a polyethylene dust explosion at a pharmaceutical supply plant in Kinston, North Carolina killed six workers and injured 38, destroying the entire 302,000-square-foot facility. The blast was felt 25 miles away. The fire burned for two days.

The CSB investigation found that fine polyethylene dust had been drifting above a suspended ceiling for an extended period of time, accumulating unseen while workers coated rubber components with plastic powder on the production floor below. The company had never conducted a combustible dust hazard assessment. It had never consulted the NFPA fire safety standard that directly applied to its operations. Perhaps most troubling, OSHA had inspected the plant just three months before the explosion, found 22 serious violations, fined the company $10,000—and never identified the dust explosion hazard that would soon kill six people.

Just three weeks later, in Corbin, Kentucky, a resin dust explosion at an automotive insulation plant killed seven workers and injured 37. The CSB investigation found that management knew the dust could explode but never told workers. The state fire marshal's office had never inspected the 32-year-old facility. Insurance company inspectors had visited repeatedly over eight years without identifying the hazard. A jury later awarded $122 million to CTA Acoustics Inc. against the resin supplier, which had knowledge of a prior fatal dust explosion involving the same material but never warned its customers.

Seven months earlier, in Vicksburg, Mississippi, a rubber recycling plant explosion resulted in the deaths of five workers. OSHA's investigation found that the company had already been cited for the exact same housekeeping and electrical violations that caused the fatal blast—and had chosen not to correct them.

At a polymer processing plant in New Jersey, a dust explosion in 2007 revealed dust accumulations up to two inches thick on walls and ceiling beams. OSHA fined the company $7,500. One year later, a second explosion at the same facility severely burned a worker. A court later found that the company's leadership had acknowledged in writing that the plant needed explosion-proof electrical wiring but made a deliberate decision not to install it, concluding it was more economically sound to leave workers at risk than to repair the facility.

These incidents aren't outliers. They represent a documented, recurring pattern: dust accumulation that goes unmanaged, safety systems that are absent or inadequate, warning signs that are ignored, prior citations that go uncorrected, and management decisions that prioritize production and cost savings over worker safety.

When Warning Signs Are Ignored

For workers, a plastic dust explosion can seem like it came out of nowhere. But the reality is that these events can almost always be predicted—and prevented. Nearly every major investigation has found that clear warning signs preceded the disaster, signs that were visible, documented, or both, and that employers failed to act on.

These warning signs might look like:

- Visible dust layers on equipment, walls, and overhead structures

- Frequent equipment jams and overheating bearings

- Small fires, flash events, and "puffs" from dust collectors

- OSHA citations or insurance company recommendations that go unaddressed

All too often, these are treated as routine nuisances rather than investigated as near-miss events. The CSB has identified this as the "normalization of warning events," a pattern where facilities experience small fires and near-misses repeatedly and, rather than recognizing them as precursors to catastrophe, accept them as a normal part of operations. In one documented case, a manufacturing plant experienced four separate dust collector fires before an explosion left a worker with third-degree burns. Each prior fire was an opportunity to identify and address the hazard. Each was ignored.

20+ Years of Regulatory Inaction

The regulatory landscape surrounding combustible dust is, itself, a failure that contributes directly to these disasters.

In 2006, the CSB published its landmark Combustible Dust Hazard Study, documenting the scope of the crisis in detail and issuing a clear recommendation: OSHA should create a comprehensive combustible dust safety standard for general industry. The study also found that 41% of Material Safety Data Sheets for known combustible materials didn't even warn users about explosion hazards, meaning many employers couldn't assess a risk they were never told existed.

What followed was two decades of regulatory stalling. OSHA launched a Combustible Dust National Emphasis Program in 2007, which was essentially a targeted inspection initiative, not a binding safety standard. After the catastrophic Imperial Sugar explosion killed 14 workers in 2008, OSHA began formal rulemaking in 2009. The required regulatory review panel was then postponed several times over the following years. In 2017, OSHA withdrew the rulemaking entirely, citing resource constraints.

The CSB took the extraordinary step of declaring OSHA's response to its recommendations "open – unacceptable," among the harshest criticisms one federal agency can direct at another. As of early 2026, nearly 20 years after the original recommendation, no comprehensive federal combustible dust standard exists.

Without a dedicated standard, OSHA is forced to enforce combustible dust safety through a patchwork of general housekeeping rules and the General Duty Clause of the Occupational Safety and Health Act. This is a weaker legal tool, as it can be harder to prosecute, subject to more legal challenges, and unable to support criminal penalties even in cases where workers are killed. Data from OSHA's own rulemaking analysis show that 24% of combustible dust citations rely on the General Duty Clause.

The National Fire Protection Association's consensus standard, now consolidated as NFPA 660, effective December 2024, provides detailed, specific safety requirements for managing combustible dust. But as a voluntary industry standard, it lacks federal enforcement power. Facilities can ignore it without legal consequence unless a state or local authority has independently adopted it.

The result is a regulatory system that is almost entirely reactive, where enforcement follows explosions rather than prevents them.

Plastics Recycling: A Growing Industry with Growing Risk

This regulatory gap is especially concerning given the rapid growth of the plastics recycling industry. The U.S. recycled plastics market reached approximately $52.85 billion in 2024 and is projected to exceed $131 billion by 2034. That growth means thousands of new facilities processing plastic at scale, generating combustible dust in the process.

Recycling operations face every dust explosion risk that traditional manufacturers do, plus several unique hazards. Mixed and unknown plastic waste streams create unpredictable dust compositions. A 2024 peer-reviewed study found that more than 90% of polymer dust samples tested from recycling operations were combustible, and that mixed polymer dusts can actually be more explosive than pure polymers. Contaminants commonly found in recycling streams, such as lithium-ion batteries, aerosol cans, and metal fragments, introduce ignition sources that traditional manufacturers rarely encounter.

Regulatory Gaps Increase the Danger

The regulatory picture is even bleaker. The federal government does not regulate plastics recycling as a unified system, and, as of late 2025, at least 25 states have passed laws reclassifying "advanced recycling" as manufacturing rather than waste disposal, potentially subjecting it to less oversight, not more. When OSHA conducted 58 comprehensive inspections of scrap and recycling facilities between 2013 and 2020, the overall compliance rate was just 16.7%. More than four out of five facilities were non-compliant with basic combustible dust safety practices.

The consequences are clear. An estimated 5,000 fires occur at U.S. waste and recycling facilities each year. In 2023, a plastics recycling warehouse fire in Richmond, Indiana—at a building packed floor-to-ceiling with plastic and lacking sprinkler systems—forced the evacuation of 2,000 residents and cost the EPA $3.3 million in cleanup. The facility had been cited for violations since 2019.

How Safety Systems Break Down

The protective measures that prevent dust explosions are well established and codified in safety standards that have existed for decades. NFPA 654, the standard specifically addressing fire and explosion prevention in plastics manufacturing, was originally adopted in 1943. The knowledge is not new.

Effective combustible dust management requires:

- Proper dust collection and ventilation systems

- Explosion venting and suppression equipment

- Grounding and bonding to control static electricity

- Regular and thorough housekeeping

- Formal dust hazard analyses

- Hot work permit programs

- Proactive equipment maintenance

- Meaningful worker training on dust hazards

These systems break down not because workers fail to follow them but because of decisions made at the management and ownership level. Production pressure leads to delayed or skipped cleanup. Cost concerns lead to belated equipment upgrades and understaffed maintenance programs. Housekeeping is treated as a low-priority task rather than the critical safety function it is. Dust hazard analyses, required by NFPA since 2016, are simply never conducted, and known hazards go unaddressed.

When explosions inevitably happen, companies sometimes frame the events as accidents caused by human error, pointing to worker actions rather than the system-level failures that created the conditions for disaster. But when investigations consistently find that dust buildup went unmanaged, safety equipment was absent or broken, warning signs were ignored, and prior citations went uncorrected, the responsibility lies not with the workers on the floor but with the decisions made by those above them.

The Human Cost of Plastic Dust Explosions

Workers who survive plastic dust explosions face devastating, life-altering injuries, with the most common being severe burns covering large portions of the body. Survivors endure months or years of painful treatment, repeated skin grafts, permanent scarring and disfigurement, respiratory damage from inhaling superheated air and combustion products, and lasting psychological trauma. Burn injuries are among the most expensive and painful injuries to treat, with medical costs alone often reaching six figures.

Many survivors are unable to return to their previous work. Families of workers who are killed lose not only a loved one but often their primary source of income and stability. These are not abstract statistics. They are real people who went to work on an ordinary day, not knowing that the conditions that would ultimately injure or kill them had been building for weeks, months, or years.

Known Hazard. Known Solutions. Missing Accountability.

The science of plastic dust explosions is thoroughly understood. The safety measures that prevent them are proven, well-documented, and available. The patterns behind every major incident have been identified, studied, and published by federal investigators. None of this is new information.

What is missing is accountability. The federal government has spent roughly two decades failing to enact a binding combustible dust safety standard despite its own investigators' urgent and repeated recommendations. Employers continue to operate facilities where explosive dust accumulates unchecked, where safety systems are absent or broken, where small fires are shrugged off as normal, and where workers are never informed that the fine powder coating every surface around them could kill them.

The rapidly growing plastics recycling industry is adding thousands of new dust-generating operations with even less oversight and lower compliance rates than traditional manufacturing. And nearly every investigation traces the cause back to employer decisions, decisions to skip safety assessments, to delay equipment upgrades, to ignore prior citations, and, above all, to prioritize production schedules and cost savings over the people doing the work.

These explosions are not accidents. They are the foreseeable consequences of choices made by companies that knew, or should have known, the risks they were imposing on their workers. This is unacceptable, and the companies responsible must be made accountable.

- Categories