Inside the Fireball

The Workers' Account of the 2013 Williams Olefins Explosion in Geismar, LA

Though these events are public record, the names of individuals involved have been changed to preserve their privacy.

It was still relatively cool at the plant the morning of June 13, 2013. It was going to get into the low 90s later that day, and it was going to be a humid one. But for now, at 8:30 am, it was fairly mild. Jorge was working his machine, waiting for the first morning break scheduled in just a few minutes.

Jorge was from Florida, but he moved to Louisiana to find work. He'd started working at the Williams plant in Geismar to support his family, but it ended up being a good job. It paid well, and it was important work—olefins are sometimes called "the building blocks of the modern world" because so many products rely on them. He worked with guys he cared about, and most importantly, it helped his family pay the bills. Like many of his coworkers, he had no reason to believe he'd ever leave the job.

Then it was 8:36 am.

Jorge Felt a Boom Ripple Through His Chest

He turned around to see where the blast was; behind him, a massive fog rolled upward and outward like a wave hurtling in every direction.

Gas, he thought.

He yelled at the guys on the ground to head for the exits.

But as Jorge was trying to get down from his machine, another explosion—this one much closer—tore through the area. The blast threw him ten feet away, tossing him between some pylons they'd erected just days earlier. He curled up on the ground, caught. He looked up to see a fireball that filled his field of vision.

He took shelter among the pylons and hoped he wouldn't burn to death.

Pressure, Panic & Pain

In an explosion, the first thing a person feels isn't heat—it's pressure. The blast creates a wave of pressure that passes through the body, forcing the air out of the lungs and rupturing the eardrums. The brain, suspended in fluid, is subject to the same pressure wave as it strikes against the skull. That wave of pressure can bounce off surfaces and equipment, hitting the same person multiple times with potentially fatal force. One explosion can feel like several. Pressure makes it difficult to catch a breath, leaving bystanders gasping for air.

- Just 1 psi can shatter a glass window.

- 5 psi causes serious injury.

- 10 psi is almost guaranteed to be fatal.

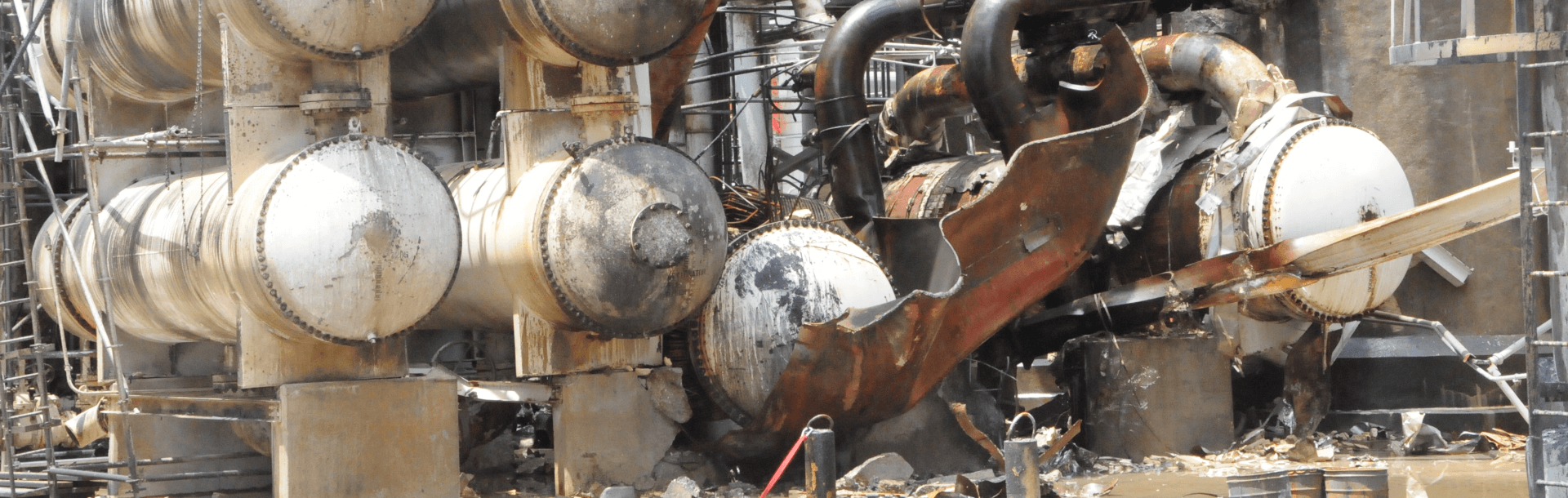

At the blast site where a reboiler tank exploded, the force was 1,200 psi. The force of the explosion (and the severe drop in pressure that follows) can launch people several feet—like it did to Jorge. Every loose piece of debris turns into a projectile, lacerating skin, muscle, nerves, or major arteries.

It's terrifying for a human being to be remotely near an explosion, much less within a few dozen yards of the blast site. Bruce, another worker at the Williams Olefins plant in Geismar, remembered a feeling of overwhelming panic. People were "running like chickens with no heads," he said.

That Panic Is Part of the Danger

People are working dozens of feet in the air at a plant like Williams Olefins, so coming down quickly presents its own risks. Brenda, a contractor and welder who was only 10-15 yards from the blast, had to climb down a pipe rack and multiple 10-foot ladders to get away. In the rush to get down, she slipped and fell, grievously injuring herself. Brenda, Jorge, and Bruce survived their ordeal, but they were among 167 workers that day who were injured by the enormous blast. They would learn later that two of their coworkers were killed.

Pain & Changes in Their Bodies

In the weeks and months that followed, Brenda, Jorge, and dozens of others noticed changes in their bodies. Their backs didn't heal as quickly or as fully as they might have hoped. The physical pain of daily life became nearly impossible to manage. The pressure wave from the blast caused multiple bTBIs, or "blast-induced traumatic brain injury." Historically, bTBI is difficult to study because it has overlapping symptoms with PTSD: poor decision-making, amnesia, headache, confusion, memory loss, mood changes, and insomnia.

Then there were the nightmares.

Like many workers after a traumatic event, Jorge was haunted by the memory of his experience. The screaming, the confusion, the certainty that he would die.

It's not uncommon for explosion survivors to bear deep scars, both psychological and physical.

But the nightmare wasn't just trauma—the Williams survivors were dealing with practical fears too. The longer they were out of work, the longer their households went without income; many plant workers are the primary breadwinners for their families. Nearly all of them reported not having enough money to get by while recovering.

"It's terrifying," said Matt, another Williams survivor. "You don't know what you're gonna do, you don't have any money coming in. You don't know what the future holds, especially when you have a family to support and you're the only one that works. It matters." Matt suffered a severe back injury, but though he'd been seeing a company doctor, things weren't getting better. It dawned on him that he might be in severe pain for the rest of his working life, but what choice did he have? His family had to eat.

For Bruce, his physical pain was only part of the picture. He was terrified of going back to the Williams Olefins plant. Brenda could barely walk, much less weld. Jorge was seeing the company-approved doctor, but he didn't trust the care he was getting. None of them knew what had caused the explosion. It was still under investigation, but Williams would never take responsibility. The blame was going to fall on the team, a manufacturer, or worse: it would be labeled a "freak accident"—something no one could have predicted or stopped.

They couldn't return to a place where something like this could happen again. Their bodies wouldn't let them.

Williams Goes Cold

Then they noticed the same shift in behavior from Williams: the company suddenly went cold. Their calls went unanswered, people they needed to speak to were never available, and there was a sense that they weren't a person anymore—just a number. The message was getting clearer: get back to work, or quit. In a revealing deposition with the then-CEO of Williams Companies, when asked if he had the power to grant relief to the workers whose lives were destroyed in the aftermath of the explosion, he denied it.

“I’m the CEO of the company. I have a board of directors that has the responsibility to make sure we’re looking after the shareholders and all of the stakeholders of the company. So, I don’t take the practice of going around and handing out money from our company’s resources that would be taking away from our investor base for no good reason.”

- Former CEO of Williams Companies

For no good reason.

That’s what these people were facing: a company that saw them as little more than liabilities, as assets gone bad. A company that saw their lives as disposable, not worth even a small part of the company’s $75 billion valuation at the time. Brenda knew the drill. She expected that the company would ask them to come to work, and then they'd be written up enough times until they could be credibly fired. They increasingly felt they were facing an enormous machine with no leverage, money, or health.

Finally, Matt and some of the others got the official call: return to work. Their bodies were broken, their minds were still trying to process what happened to them, and they were facing a mountain of medical bills—probably for the rest of their lives. Yet Williams asked them to return as though they'd all taken an extended vacation.

That's when they all arrived at the same conclusion: "I need a lawyer."

The History of Williams Olefins

Founded in 1908, The Williams Companies, Inc. (known then as Williams Brothers) has been one of the largest petrochemical companies in the world for nearly its entire existence. In 1967, it bought the largest petroleum products pipeline in the United States for $287 million. That marked the beginning of a massive consolidation of natural gas and petrochemical assets under the Williams brand, including an olefins plant in Geismar they bought in 1999.

Their expansion included a plan to upgrade the productive output of the Geismar plant from 600 million pounds of ethylene a year to over 1.2 billion pounds a year. In 2001, Williams commissioned an upgrade of the reboiler system to reduce downtime and keep the factory constantly running throughout the year while undergoing maintenance.

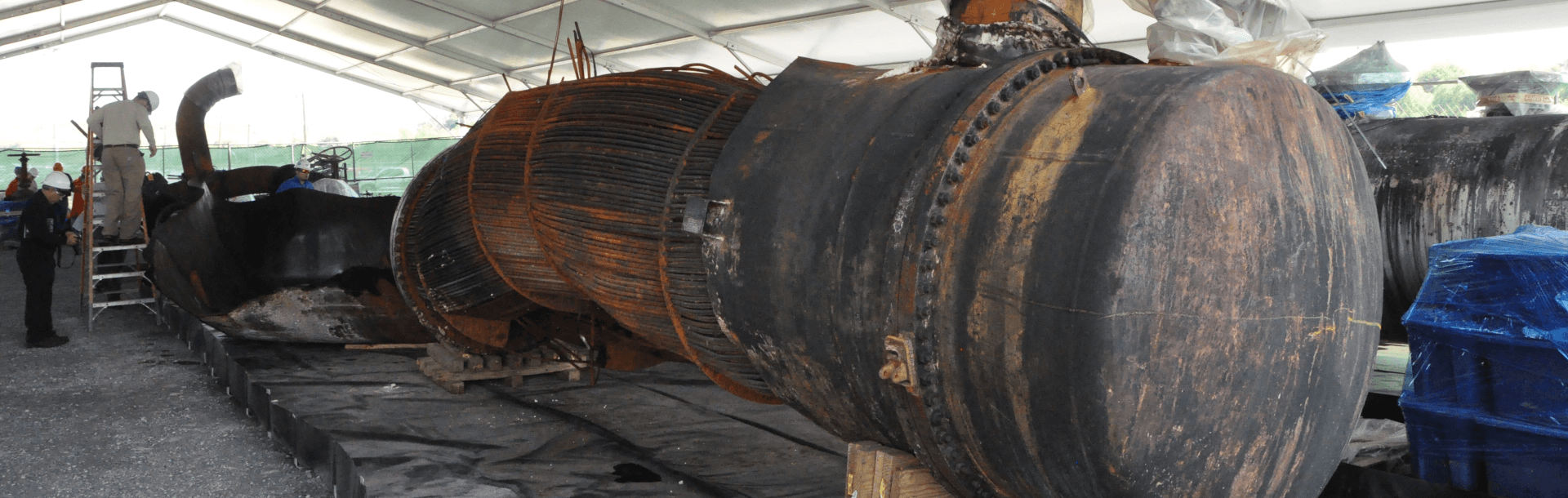

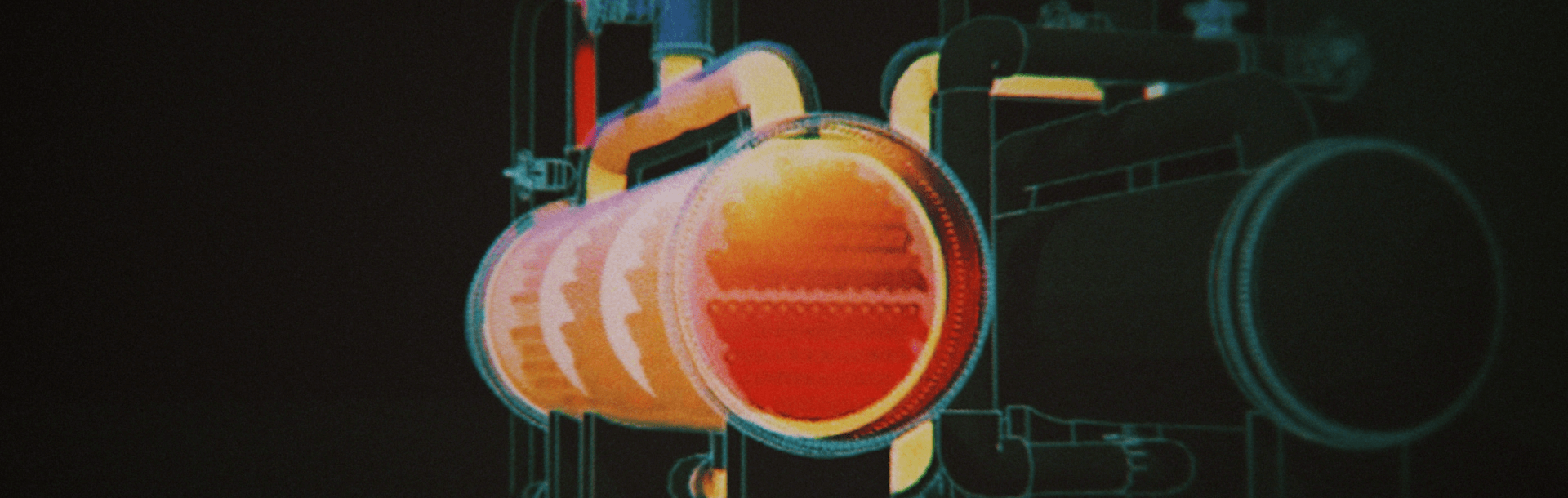

The reboilers were 24-foot tanks filled with water and propane (separated by a network of tiny pipes). The hot water would heat the propane, sending it into a distillation column. However, the water that feeds the tanks is filled with tar, so the tanks would periodically "foul," becoming clogged so that hot water could no longer cycle through. Cleaning the tanks required shutting down production completely. Williams higher-ups had the idea that if you could isolate each reboiler, you could clean one tank while running water through the other. The entire plant could keep running. So, four valves were added to each reboiler: an entrance and exit valve each for both water and propane.

Typically, an upgrade like that is preceded by documentation explaining the potential hazards and conditions of such a change to the system. But Williams decided to install the upgrade and write the documentation later. As a result, the documentation missed a crucial detail about the upgrade. It would lie in wait for 12 years.

Preparing for the Battle Ahead

"I didn't think I was gonna get any results."

- Brenda, Williams Olefins Worker

"I didn't think I was gonna get any results," Brenda said about her decision to call a lawyer. All she knew was that she'd need someone in her corner if she was going to protect herself from Williams. Most plant workers are reluctant to sue their employer; many of them have built their entire lives around a good job with a generous paycheck. Their bosses and managers are people they've worked with for years. But many plant workers like Brenda have also seen what companies do to people who've been seriously hurt at work. At first, it's all sympathy and condolences. Then, as time stretches on, the sympathy fades. The expectations rise to unfair levels. Hurt workers are subjected to drug tests and enhanced scrutiny.

Then, one day, they get fired—left with no career, no prospects, and a lifetime of chronic pain.

Faced with that possible future, they do what anyone else would do: they protect themselves.

Word spread.

A number of the guys at the plant started going with different lawyers around town. Over 100 went with a Houston personal injury law firm called Arnold & Itkin, a team that made headlines representing survivors of the Deepwater Horizon explosion in 2010. They also represented workers who survived the plant explosion at the Texas City BP facility in 2005.

No one knew it at the time, but Arnold & Itkin's investigation of the Texas City BP explosion would prove to be deeply relevant to the Williams case.

Like Texas City, the Geismar explosion came down to a faulty valve.

Complete & Total Denial

The Williams Companies, Inc. owned the Williams Olefins plant through a shell company of the same name. So, their legal strategy was simple: claim that Williams Olefins LLC bore all the responsibility for the accident. Then, the parent company—a Fortune 500 company—could not be made to pay for what happened. Fortunately for Williams executives, Williams Olefins LLC barely had any assets to its name on paper. There's no way the child company could offer relief to the 167 injured survivors and their families.

The survivors and their lawyers would need to prove that The Williams Companies, Inc. was playing a shell game—that they were in charge of the plant's operation and upgrade projects all along and that they were hiding behind an empty child company to evade accountability. They would also need to do it several times over. Arnold & Itkin alone represented over 100 workers, with a small group of workers per trial.

Dozens of trials and years of litigation lay ahead.

But all of it was riding on the first two trials, scheduled to begin within weeks of each other. Even the largest law firms work for months around the clock to prepare for one trial.

Arnold & Itkin, with a relatively small staff, would need to prepare for two.

Williams offered no settlement, signaling that they were confident they would win these first two trials, which would severely dampen the hopes of the remaining survivors.

In short, a lot was riding on the investigation into what led up to June 13.

Cascading Failures of Safety & Responsibility

This is a brief timeline of what happened between Williams acquiring the Geismar plant and the June 13 explosion:

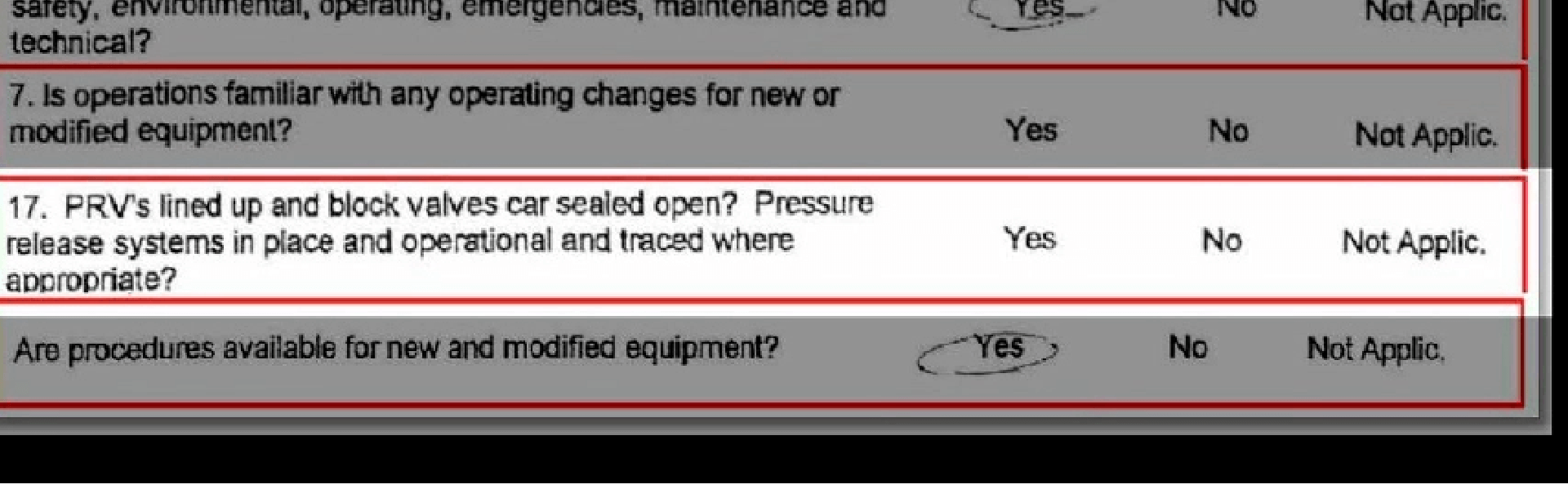

- In 2001, The Williams Companies, Inc. isolated the reboiler system to allow for an aggressive expansion of the plant's productive capacity. One reboiler would be kept inactive until the other required cleaning, and then the system would switch over without interrupting production. Multiple employees saw a major flaw in the reboiler system's design: there was no safety release valve.

- In 2006 and 2008, both internal and external sources recommended installing car sealing open reboiler block valves, which would allow automatic pressure relief to both tanks. In 2010, the recommendation was only carried out halfway—only the active reboiler received a car seal. For unknown reasons, a written report of the upgrade said both reboilers received a car seal, but the inactive one, Reboiler B, was left alone.

- In 2012, a new procedure was written to make sure the inactive reboiler would remain inert. Reboiler B was filled with nitrogen (a stable gas), and all its valves were shut, but there was one problem: the valves were known to leak. As a result, Reboiler B slowly filled with propane, which displaced the nitrogen. The truck-sized tank had become a time bomb.

- A few months later, in May 2012, Williams Olefins had one more chance to correct their mistake. An engineering records coordinator discovered that Reboiler B was missing the crucial relief valve. The records were updated, but the whole plant was about to undergo yet another expansion, this time to the tune of $400 million. Experts and managers at Williams Olefins urged the CEO and Board of Directors of The Williams Companies that a full shutdown of the plant for a few months would be safer, but the executives dismissed those concerns. The plant would remain operational during the massive construction project.

Installing a car seal on Reboiler B would have taken a few minutes and cost $5. It never happened. Instead, on June 13, 2013, in the middle of the expansion project, water was released into Reboiler B. It heated the propane gathering there for over a year, but because there was no car seal, the propane had nowhere to go. It only took three minutes for the pressure to trigger a catastrophic explosion.

The Williams Companies knew there were serious risks to operating the plant. Their decision to expand while remaining operational is a key reason the reboiler exploded at all. Executives at the parent company were key decision-makers over the expansion project. There's no question that they were responsible.

Vindication Before a Jury

For the survivors, it was eye-opening to see how the worst moment of their lives was caused by corporate negligence. Multiple employees and contractors warned Williams that something would go wrong if they continued cutting corners while expanding rapidly. Safety concerns were ignored. Key procedures were skipped or done out of order. And yet, Williams pressed on—causing unspeakable and irreversible harm to an entire community.

As trial approached, Williams declined to settle.

Everything depended on whether the jury would see the truth.

Three weeks passed, with survivors providing testimony and Arnold & Itkin offering evidence that The Williams Companies were in control of the operation all along.

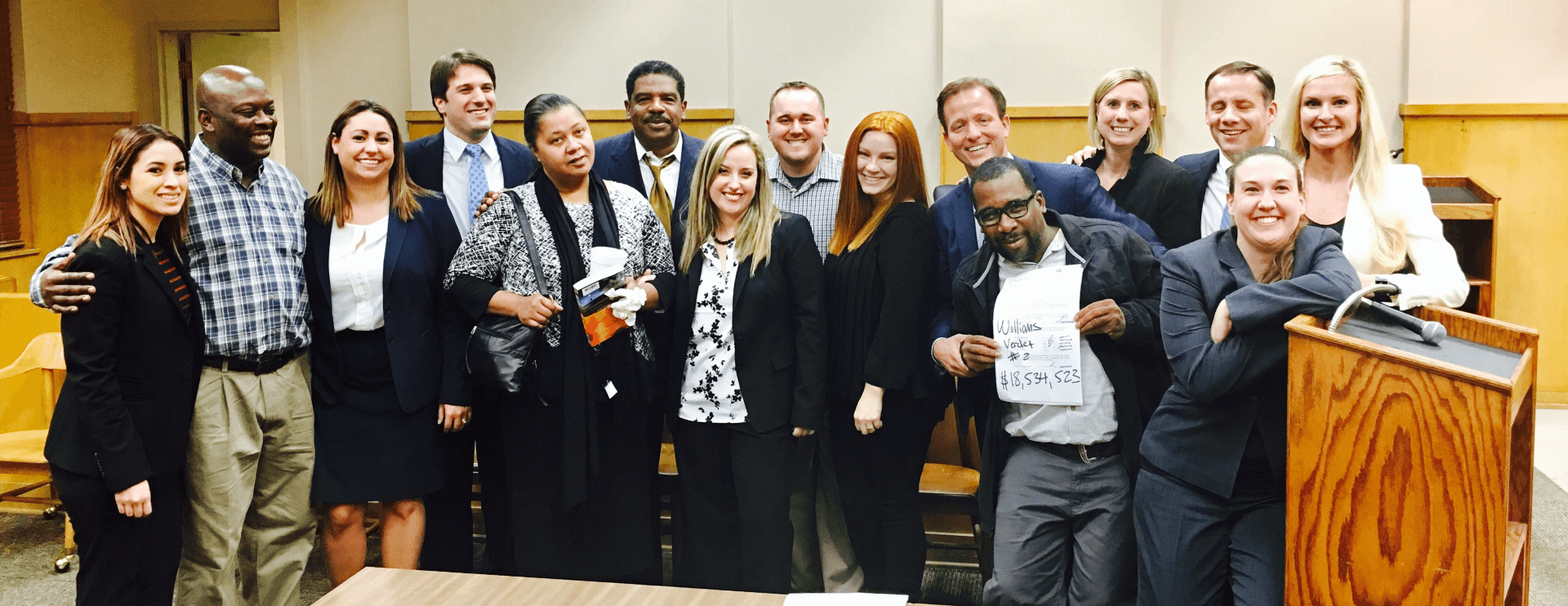

The jury deliberated, handing down a verdict of $15.5 million.

Then, unable to rest or recuperate, the firm immediately prepared for yet another trial scheduled to begin in a few weeks. Williams continued to refuse to settle.

The second jury handed down a verdict of $18.5 million.

That's when it became clear to Williams: juries were going to side with the workers. They settled with the rest of the workers for a confidential amount.

The Long Nightmare Ends

Matt says he'd hate to think where he'd be if Arnold & Itkin hadn't beaten Williams in court. "I'd probably be working with a hurt back," he said. Instead, he's able to spend more time with his family and manage his pain in peace. Jorge was able to provide for his family, allowing them a permanent place to live. The same is true of Bruce, Brenda, and the dozens of coworkers and teammates who faced the same fiery nightmare and lived. They fought against one of the largest companies in the United States and won, but for most of them, the biggest victory comes from being able to recover at their own pace.

"I'm not 100%, but hopefully I won't ever have to go back there again. If [Arnold & Itkin] hadn't been involved, I probably would be trying to work on someone else's job in the condition that I'm in. I probably would have been messed over."

- Brenda, William Olefins Worker

There are millions of work-related accidents every year. Many of those workers felt the same way the Williams survivors did: without recourse, without options, and low on cash. All of their stories echo the ones written here. Many of them end up going back to work because they don't have a choice.

The negligent safety decisions made by industrial executives have a profound and lasting impact on real people. But sometimes, the relentless effort of a few lawyers, paralegals, and support staff can have just as profound an impact.

“Arnold & Itkin knows everything there is to know about plant explosions and how to win against big corporations. I saw it firsthand in the courtroom. If anyone other than Arnold & Itkin and my firm had been trying these cases, these families would have never gotten the top-dollar results they did. In fact, they may have ended up with nothing. Together we really helped these people get a better future.” — Tony Clayton, renowned litigator and collaborator with Arnold & Itkin

While the Geismar explosion was a tragedy, it's also proof to large companies that these survivors' voices, their lives, ought to matter more than expanding an aging petrochemical plant.

That's worth fighting for.